Password authentication

Introductions

- introductions of two students

Questions on the readings

The readings today are from Computer Security and the Internet, Chapter 3, sections 3.0 - 3.2, 3.6, 3.8.

Password authentication

-

Never store passwords as cleartext — if your password database is stolen, the attacker now knows all passwords and can try them on other sites

- instead store hash of the password, using a cryptographic hash function

-

basic operation

- generate a random salt

- generate a hash of the password and salt hash = H(password, salt)

- store username, salt, hash

- note, often the hash includes an encoded salt to simplify storage

Attacks on passwords

-

offline vs online attacks

- offline — steal a password database (username, salt, hash), try to crack them, usually using a GPU

- online — guess passwords on a live system

-

rainbow table attack

- user a list of potential passwords (possibly from a breach list)

- pre-compute hashes for a well-known hashing algorithm

- steal a password database

- compare pre-computed hashes to the password database

- fast attack since precomputation used

- foiled by use of salt, which is why salting is so important

-

dictionary attack

- use a list of potential passwords (possibly from a breach list)

- for each password, compute the hash for each user, using their salt

- look for a match

- computation must be done separately for each user since they each have a different, randoms salt

- no precomputation can be done since salts not known in advance

-

password capture

- shoulder-surfing

- keyloggers

- malware

- phishing

- social engineering

-

password interface bypass

-

defeating recovery mechanisms

Password policies

-

policies recommended by NIST guidelines, see 3.1.1.2

- minimum length of 8, should use minimum length of 15

- accept all printable characters

- check registered passwords against blocklists

- rate limit password guessing

- could also use a pepper — like a salt, but stored separately, e.g. in an HSM (hardware security module)

-

policies no longer recommended by NIST, see Appendix A for helpful details

- password complexity requirements (users will just make “Password1!”)

- password should not arbitarily expire — only expire if evidence of a compromise exists

- hints that are available to an unauthenticated user

Length and complexity requirements beyond those recommended here significantly increase the difficulty of using passwords and increase user frustration. As a result, users often work around these restrictions counterproductively. Other mitigations (e.g., blocklists, secure hashed storage, machine-generated random passwords, and rate limiting) are more effective at preventing modern brute-force attacks, so no additional complexity requirements are imposed.

Notice that this shifts the burden from the user to the system

Recommended hashing algorithsm

-

Argon2id

- Argon2 — resists GPU cracking attacks (because it slows them down)

- Argon2i — resists side-channel attacks

- Argon2id — combines them both

-

scrypt if Argon2id is not available

-

bcrypt only for legacy systems

-

PBKDF2 for FIPS-140 compliance (cryptographic modules)

Entropy

- user chosen passwords are not random

- entropy is often misused for passwords, leading to poor conclusions about password security

Bad example (taken from an unnamed website)

E = L×log2(R)

- E is your password entropy

- R is the possible range of character types in your password

- L is the number of characters in your password (its length)

| Example | Character Range | Password Length | Calculation | Bits of Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bankruptcies | 52 | 12 chars. | E = 12 x 5.7 | 68.4 |

| 1Bankruptcies2 | 62 | 14 chars. | E = 14 x 5.95 | 83.3 |

| 1Bankruptcies2&% | 94 | 16 chars. | E = 16 x 6.55 | 104.8 |

- Generally, a strong or high-entropy password scores at least 75 bits. Anything measuring fewer than 72 bits is reasonably easy for a machine to crack.

Why this approach is misleading

- assumes attacker goes through every possible password, methodically

- in reality, attackers try high probability passwords first

- assumes users choose passwords randomly from the entire password space (e.g. c1Bkanpurtis2&e% is just as probably as 1Bankruptcies2&%)

- in reality, an attacker can use a dictionary, add in capitals, numbers, and digits, and get to this guess much faster than the calculated bits of entropy would imply

- all the shown passwords are relatively easy to guess

Password managers

-

features

- store passwords

- generate random passwords

- autofill passwords

- sync passwords among your devices

-

protected by a master password

-

security and risks

- single point of failure

- master password capture, online guessing, or offline guessing

- risk if password manager fails

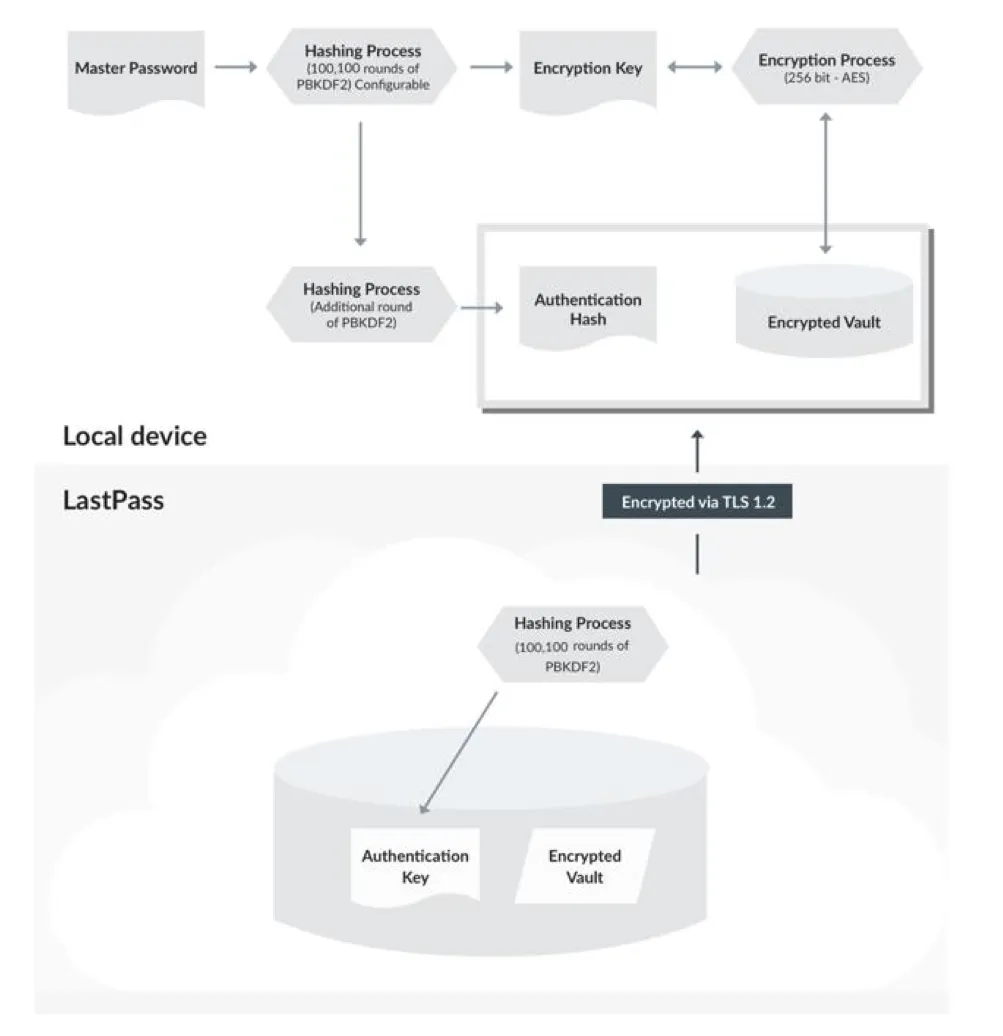

Lastpass

-

puts your master password through a key derivation function, PBKDF2, for many rounds

- this results in an encryption key that is used to encrypt the password vault, using AES

- one more round of the KDF provides the authentication hash

-

key point: if an attacker steals your vault (which has happened with LastPass), and you used a weak master password, they can brute force that password to recover your vault

-

see LastPass Technical whitepaper for more details

1Password

-

uses an additional secret key that is mixed with the password

- k = PBKDF2(password, secret_key, 650000)

- to decrypt your vault, you need (a) password, (b) secret key, (c) encrypted vault

- prevents a brute-force attack on your vault if it is stolen

-

this means you need to store the secret key safely and then enter it to authorize a new device to access your vault

- 1Password recommends printing and storing it somewhere (they call this the Emergency Kit)

-

see 1Password Security Design for more details

Extra reading

Password policies and system administrators

- see An Administrator’s Guide to Internet Password Research — note, predated NIST by 6 years

Password alternatives

- The Quest to Replace Passwords

- considers security, usability, and deployability

Not only does no known scheme come close to providing all desired benefits: none even retains the full set of benefits that legacy passwords already provide. In particular, there is a wide range from schemes offering minor security benefits beyond legacy passwords, to those offering significant security benefits in return for being more costly to deploy or more difficult to use. We conclude that many academic proposals have failed to gain traction because researchers rarely consider a sufficiently wide range of real-world

password managers

-

Why Do People Adopt, or Reject, Smartphone Password Managers?

- lack of awareness

- belief that current practices are secure

- difficulty using or understanding them

- worry about lack of control

-

Why people (don’t) use password managers effectively

- trade-offs between security and convenience (e.g. prioritizing random passwords on financial accounts)

- users of built-in password managers more motivated by convenience (and have more re-used passwords), users of separate password managers driven by security

-

Why Users (Don’t) Use Password Managers at a Large Educational Institution

- 77% use a password managers, 60% using built-in (browser based), 18% using third party

- 77% reuse passwords across accounts, but those using third party password managers are much less likely to do that

- ease of use more important than security

- third-party password manager users are significantly more likely to use the password manager to generate random passwords

-

- identifies some weaknesses in password managers

-

- many using them for convenience, not sucurity

- users add credentials as they visit websites, and prioritize the sites they add

- users update passwords only when they are considreed insecure

- distrust of password managers, so some users don’t store important passwords there